Upon arriving in Guangdong City, martial arts master Wong Yin-Lum erected a large wooden stage and announced that he would accept any challenger to prove the effectiveness of lion's roar, which he learned from Lama Sing Lung (Sage Dragon). At the time, the city was southern China's martial arts proving ground and as such, challenges were not taken lightly. Matches had no rules and no restrictions; permanent injury and death were common. Upon arriving in Guangdong City, martial arts master Wong Yin-Lum erected a large wooden stage and announced that he would accept any challenger to prove the effectiveness of lion's roar, which he learned from Lama Sing Lung (Sage Dragon). At the time, the city was southern China's martial arts proving ground and as such, challenges were not taken lightly. Matches had no rules and no restrictions; permanent injury and death were common.

During the following weeks, 150 of the area's top fighters were bested, some in a matter of seconds. Such dominance was unprecedented, and it earned Wong Yin-Lum great honor and fame and a place among the Ten Tigers of Guangdong.

The Lion's Roar Art

The lion's roar system of kung-fu is based on the movements of a gibbon (ape) and a black sarus crane. Ape techniques contribute the intercepting and deceptive use of footwork, and the circular hand and arm techniques whose momentum delivers exceptional destructive power. The crane movements consist of more precise and stylized movements. However, the techniques from both animals stress the fundamental principle of keeping the hands away from the body. This makes the art visibly different and its approach counterintuitive, seemingly vulnerable and even awkward to the uninitiated. However, it is a dreadful mistake to think that with lion's roar, "What you see is what you get."

In training, momentum and leverage are used to develop maximum speed and power. In actual combat, much of the 360-degree arcs of the punches are post-contact or follow-through. The punching trajectory or arc paths are also considerably tightened or shortened up once contact is made with an opponent's bridge (defense or guard). But what is actually achieved both mechanically and technically by keeping the hands from the body?

In mechanical terms, this allows the generation of great penetrative power. The lion's roar spinning stance (prayer wheel body) propels the arms through centrifugal force, which would be markedly reduced if the hands and arms were held closer to the body. The spinning stance provides a support base and balance, while the momentum of the arms delivers impact.

Technically, holding your arms close to your body makes you much more vulnerable to smothering-style grappling and takedown attacks. The long-armed techniques of the Tibetan lion's roar system work effectively at close range. Whole-body force is driven into the target through ramming-type stances and heavy follow-through punches. This allows for long-arm strikes even at chest-to-chest distance without spacing, and involves the principle of striking the opponent's center of gravity right from under him. It's a principle exploited to its maximum benefit by a lion's roar practitioner.

The biggest mistakes that observers make when viewing Tibetan long-armed training are to think that long armed means only long range and to believe that because they can see the techniques (from the outside looking in), then the target will see them equally clearly. However, if you ever see Tibetans training in this way, they will either be training the seeds of the system as mechanical and aerobic methods of conditioning, or as mind-body training to develop the potential latent in the techniques. The seeds of the lion's roar art act like building blocks that mesh into a bewildering array of techniques that go beyond what is apparent in their basic structure.

The blows use a variety of striking surfaces including all aspects of the fists, knuckles, fingers, palms, wrists, forearms, elbows and even the shoulders. Targets are as varied as they come; if something is within range, then it is smashed or destroyed. The strikes flow in wavelike combinations that deliver deadening contact force to large areas of the limbs and body, or to precise pressure and vital points.

The basic stance and footwork patterns act as a chassis or artillery platform for these immensely powerful attacks. Wing chun master Greco Wong describes the application of Tibetan footwork patterns as "turning their axis like an erratic compass needle." But there is a method to this madness-the torque generated by the twisting and spinning of the stance, which draws power through the feet, hips and waist, and is then delivered through the back, shoulders and on down into the arms and hands, is phenomenal.

Many also worry that the force involved is too great and that the practitioner risks damaging his hands and limbs through such terrific power. Injuries, however, are rare if proper use of form is integrated in time with the motions.

A little-known aspect of lion's roar training involves activating the primal rage within the lion's roar body by using spinning stances that afford one an almost superhuman burst of adrenaline. This often-neglected and psychological aspect to real combat is integrated from day one into the Tibetan system of training. Nevertheless, proper technique will reduce injuries and develop proper habits.

|

|

|

|

|

|

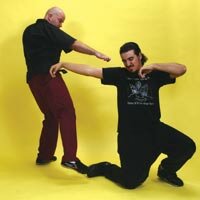

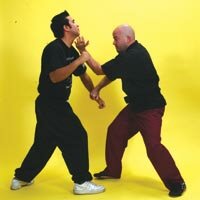

| The attacker assumes a right freestyle/streetfighting stance. The defender is in a lion's roar stretched cat stance with lama "gun-sight" guard hand (1). The defender sidesteps an incoming straight right punch (2). Note the parry against the elbow joint and the simultaneous chambering of the right "tsap choi" or stabbing fist hand. The defender launches a simultaneous kick to the side of the attacker's knee and a stabbing foreknuckle punch to the attacker's exposed ribs (3). The defender steps through the knee joint and brings the attacker to the ground (4). The defender converts the nail punch to a grab, pulling the attacker's right arm down and away past the defender's right hip. He simultaneously delivers an overhead scrapping punch (cup-choi) to the base of the attacker's neck (5). |

The Hallmark Strikes

All branches of Tibetan kung-fu-hop gar, bok hok, lama pai and si gi hao-use three essential core long-arm strikes. When combined, these three strikes are known as lau sing choi or shooting star fist. So fundamental are these techniques that an entire classical form is built around them: lau sing dar or the shooting star attack. These three jewels hallmark the Tibetan tradition by their expert application and refinement.

These strikes are:

Chune Choi (straight penetrating cut)

Pau Choi (uplifting cannon cut)

Cup Choi (downward scraping cut)

Chune Choi

"Chune" means to penetrate and "choi" means to cut. Chune refers to the principle of penetrating the target, literally right through its occupied physical space. Chune choi is not launched from long distance in real combat. With all Tibetan lion's roar attacks, the punch is long-armed but should be delivered from a short distance with force penetrating the target on the follow through. If the opponent is moving forward, then chune choi cuts through his path as he advances. If he is retreating, it penetrates his line of retreat. If he angles off the side, then it bisects his plane of movement. In practice, chune choi is a double-arm technique; the strike is launched from the rear with respect to the target, while the lead arm distracts, deflects, blocks, hooks away or strikes preemptively. During delivery, chune choi may be twisted corkscrew fashion through 90, 180 or even 270 degrees. The striking surface may be flat (i.e., with no protruding knuckles) or may take any of the style's specialized hand formations, such as phoenix eye fist or chicken heart fist. It is said in Tibetan fighting theory that all straight strikes are derived from chune choi.

The term "chune ging," meaning "penetrating power," refers to manifesting penetrative force. As a principle it can be seen that chune not only penetrates in straight paths, but also penetrates the target's structure. This is the true essence of chune choi. Having good chune ging is achieving trained strength.

|

|

|

|

|

|

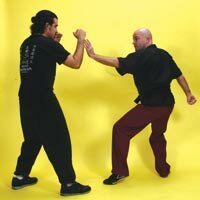

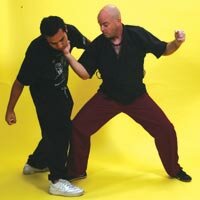

| The attacker has stepped in with a right lunging hook punch. The defender intercepts the arc of the attack by stepping through the attacker's advancing center of gravity (1). The defender's right forearm rotates inward against the twin heads of the attacker's shoulder and biceps (on the hook punching arm). This further breaks the momentum of the attack by expanding its arc. Seen from the opposite side, the defender's leg "stance-rams" the attacker's right leg above the knee. The defender's right arm simultaneously "whips" out from the vertical into a horizontal arcing backfist (bin-choi) to engage the attacker's follow-up left hook (2). The defender's left vertical blocking arm converts into a curved path punch that will straighten up for a follow through immediately prior to impact (3).The final photograph illustrates the "midpoint" in execution of a "practical" chune-choi lion's roar hallmark seed punch (4). |

Pau Choi

"Pau" means to "uplift like a cannon" and "choi" means "to cut." Pau is an upward moving long-armed strike. Like chune, choi it is delivered from a twisting but stable stance, adding momentum at the end point delivery of power. As with chune choi, the pau choi is most-often used as part of a combination arising from behind the practitioner and therefore outside his line of sight. By the time pau choi is seen there is little time to react.

Sometimes however, pau choi is used as a feeder or as a tempting or fishing hand. In such cases the punch is deliberately offered to the opponent as "slow" technique, with the purpose to fake, distract and deceive. If the opponent reacts by attempting to block, deflect or grab the pau, it immediately switches into another technique. It may also simply mask another attack from the other hand, the feet or elbows.

The most devastating use of pau choi is as a surprise attack, where the fist follows a 360-degree arc right up the opponent's midline. While this movement may sound slow or even obvious, it is quick and virtually undetectable. Basic applications of pau choi include a flailing ape-like X-lined attack aimed at large joint areas, limbs and head. As with chune choi, the pau choi can be delivered into the opponent's static space, but also into the space the opponent is about to occupy. Further, pau choi can be used on the retreat so that the attacker walks right into it. All upwardly moving hand techniques in lion's roar are derived from the pau choi seed action.

Cup Choi

The basic version involves an overhand vertical strike with what is termed "squeeze point" action. Here, the fist and arm tightens at the last moment. On impact the feet brace and arrest any turning forces working through the stance so the momentum is fully transferred fully into the target. Like pau choi, targets can include the head and limbs, as well as the torso.

This classic knockout blow can be also performed in a horizontal fashion, launched gunfighter-like from the hands placed neutrally at the sides. It can also follow from an inside block or bridge position straight across the jaw or be used as a destruction strike against the biceps muscle after slipping a lead punch from an opponent. As a feeder, cup choi is often used to entice an opponent into using rising block actions; the cup choi immediately converts on contact into a hooking hand to pull the attacker into another strike or jointlock manipulation.

Cup choi is another ape-like flailing technique that works like chune choi and pau choi to penetrate space, and likewise can intercept the space the target is moving into rather than its static position. In lion's roar, all downward actions are derived from the seed of cup choi.

The Seed Punches in Combination

Although usable in isolation from one another, the three lion's roar seed punches are also practiced as one continuously flowing combination. This is lau sing choi-the shooting star cut. The strikes are practiced with ramming stance footwork patterns designed to break the opponent's balance. Combined with this footwork, the seed punches form the essence of lion's roar combat.

|

|

|

|

|

|

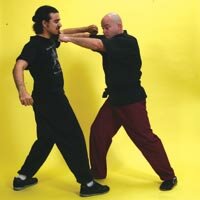

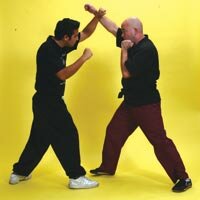

| The attacker is in left-hand guard. The defender assumes a side-facing lama gun-sight guard position (1). The defender releases a "feeder" punch in the form of a 180-degree overhead "cup choi" or "scrapping punch, intended to draw a reaction, or a direct strike the attacker. The attacker steps in to meet the feeder strike with an upward-rising forearm block (2). On contact with the blocking arm, the defender converts his overhead punch to a pulling-down action with his wrist, simultaneously converting his chambered left fist to an upward shovel palm strike (3). The defender strikes with a scraping outward crane's beak attack (4) to behind the jaw hinge (5). His pull brings the attacker into the strike. The defender twists into a powerful uppercut strike to the jaw (6). |

Christofer Arnold is an eighth-level master and the American representative for lion's roar under master Steven Richards of the United Kingdom lion's roar sangha. He lives and teaches in Palm Desert, Califor

|