|

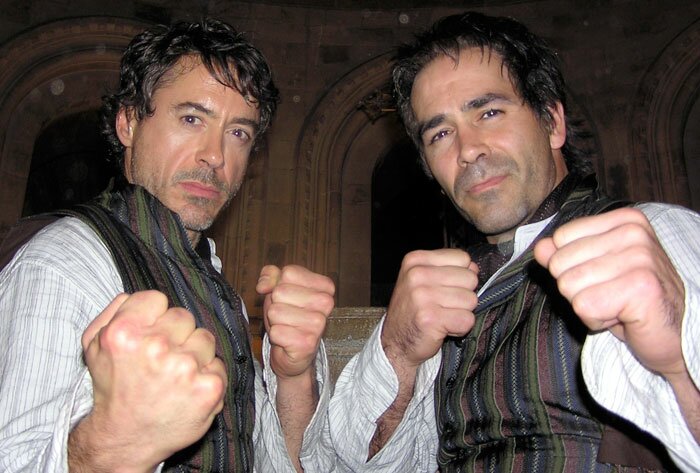

Eric Oram’s action magic in Iron Man and Sherlock Holmes is creating a new generation of wing chun fans.

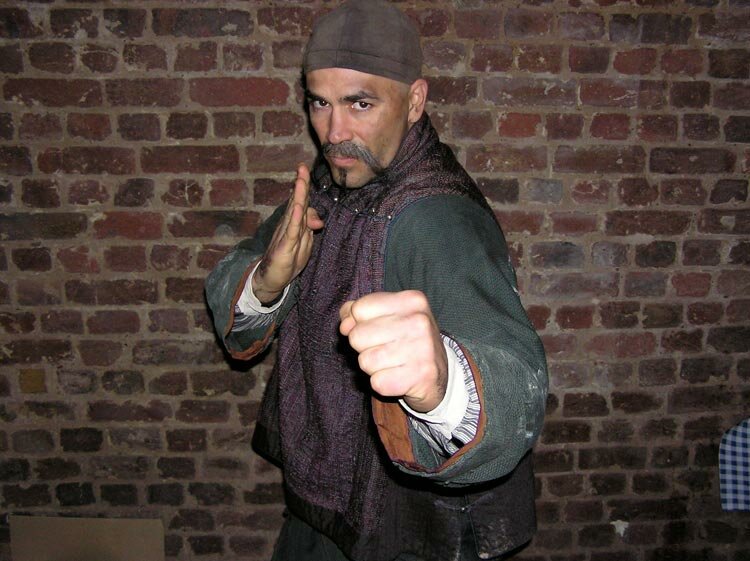

Two sheathed swords menace from a wall, while a bullwhip coils on a chair. A small bamboo plant sits serenely on a desk across from a silent computer monitor. Things inside Eric Oram’s office belie the iron will and placid composure he brought to the sets of Sherlock Holmes and Iron Man, two of Hollywood’s most-successful recent movie franchises.

“Where your mind is, is where the whip goes,” explains Oram, who’s helped the traditional martial art of wing chun kung-fu make a mainstream splash with three action blockbusters. “If your mind strays, the whip strays. This represents a mindset, to relax within the intensity; not bringing intention into tension.”

Oram’s focus is on his obligation to not only preserve the art of wing chun, but to promote its pure form. The system made famous by the late Yip (Ip) Man and his most prized student, Bruce Lee, is enjoying a resurgence thanks to the amazing fight choreography in Sherlock Holmes and Iron Man 1-2.

“For the first time wing chun was featured in a big Western film, with a big star and a big budget,” notes Oram, a senior student of grandmaster William Cheung. “Wing chun became a part of American pop culture. I believe it’s tipping now to awareness.”

This contrasts with the preaching-to-the-choir quality of Donnie Yen’s Ip Man, which broke box-office records in Asia, but is getting tepid play in the United States.

Finding a Holmes

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle immortalized the quintessential British detective in his “Sherlock Holmes” mystery novels, where he described the protagonist as being a master of “bartitsu” in 1901’s The Adventure of the Empty House. Bartitsu was founded in 1899 by Edward William Barton-Wright, a Brit born in India. Based on older forms of jiu-jitsu, bartitsu was an amalgamation of Barton-Wright’s name and jiu-jitsu, combining combat tactics from British boxing and kicking techniques, Swiss stickfighting and ko-ryu jiu-jitsu.

Bartitsu’s Academy of Arms and Physical Culture in Soho, London, closed in 1903 reportedly because Barton-Wright lacked technical mastery and promotional skills.

But Holmes’ mythical fighting prowess lives on thanks to the magic of the silver screen and a meeting nearly two decades ago between Oram and the movie’s star, Robert Downey Jr. At the time, Downey Jr. was studying with Oram’s sifu, grandmaster William Cheung, a classmate of the late Bruce Lee in Hong Kong.

“When (Downey) first came to me, he made an appointment and I thought it would probably be too hard, too intensive,” notes Oram, set to spend the next six months in England choreographing the Sherlock Holmes sequel. “I told him, ‘You won’t stick with it. You don’t have the discipline. You’re an actor.’

A Martial Artist is Born

Downey insisted and Oram agreed—10 lessons to see if the star would toe the line and jump when his sifu said “jump.”

“It’s been a constant, pleasant surprise,” Oram said of the star’s tenacity. “No matter what I throw at him, how hard I hit. I’ve knocked him down but not out.”

Along with a strained shoulder, tweaked joints and arm bruises, Oram’s given Downey two black eyes. One of them occurred shortly before Downey was to award Sting’s wife, Trudie Styler, an honor at a gala. Downey wore sunglasses during the keynote address and only took them off to make a joke about how world-renowned musician and vocalist, Sting, gave him the black eye after Downey told him he’d been looking at inappropriate photos of his wife.

Wing chun has honed Downey’s physique and constitution. “With the first Iron Man he had to mentally and physically prepare for the interview,” Oram said. “He intensified his focus and strength leading up to the screen test. At first, Marvel (Comics) didn’t see him as an action hero, but he got the part.”

Staying Sharp

Oram remained on the set of Iron Man and during breaks or between scenes the pair would fight to maintain Downey Jr.’s peak focus and energy. Since Downey was suited up for the computer-generated imagery, his movement and momentum stayed controlled for the set staging. Oram offered some guidance for moves that wouldn’t look too unwieldy or cumbersome.

Since wing chun is a close-in, centerline style, much of Iron Man’s movements violate the principles of the art, so most of the shots were filmed at a wider angle.

“Up close it would be lost,” explains Oram, who began his martial arts training at 14. “We’d have to punch the camera in. When it’s closer, it fills the screen.” Downey’s movements were much bigger and broader inside the hulking super hero suit.

“This led up to “Sherlock,” where there was no suit. He was human and more attuned to being a fighter,” Oram adds. “It was real and it was tactile, and wing chun was better than the form Conan Doyle says Holmes used as a martial art.”

In the animation-driven, first Iron Man, Oram said he felt as if he was wedged into the fight choreography team. His involvement in the Iron Man sequel and Sherlock Holmes franchise is more to his liking. He said he’s controlled how some shots look and blocked some scenes and even played minor characters.

Star Quality

The movies have attracted more celebrity wing chun students. Actors Jake Gyllenhaal and Christian Bale have been photographed leaving Oram’s West Los Angeles academy. But Oram doesn’t get caught up with their star status. “Robert’s a friend, but he’s a student first and foremost,” Oram relates.

Realizing that actors are sometimes insulated from the hard reality of everyday life Oram explains, “They come into the academy and I’m not intimidated by them. The egos can be a bit much, but there’s a quick attitude adjustment or they just quit.”

This reminds Oram, who once was a budding drummer, of his switch at age 11 from akimbo karate to wing chun three years later.

“I saw Enter the Dragon and couldn’t believe how such a small person could be so explosive and powerful,” Oram remembers. Then at 15, he was in a grueling lesson with his grandmaster. Cheung could see his student was weak and demoralized. But he refused to go easy on his young student.

“I could barely lift my arms,” Oram recalled. “He’s screaming at this point and telling me to continue, and I said to him, ‘That’s easy for you to say.’ ” Oram remembers the look on his grandmaster’s face, the one time he’s ever looked at Oram that way, but what he won’t forget is the statement: “Either you believe, right here, right now, that you are the master that you will become or there’s no point in going on.”

And that’s why Oram feels such an obligation to build on the foundation and newfound popularity of wing chun. He’s taken Downey’s 16-year-old musician son, Indio Falconer Downey, under his tutelage and hopes to harness the young man’s head-in-the-clouds energy.

The lessons he learned as a young student are being put to good use with the next generation of wing chun stylist. “Remember the saying, Oram relates, “a black sash is a white sash well used.”

Did You Know?

Eric Oram has taught Chinese boxing to the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers, Seattle Seahawks and Arizona Cardinals.

Where to Find Eric

Eric Oram founded the Wing Chun Academy & Mind/Body Center in West Los Angeles. For more information, visit www.lawingchun.com or .

About Wing Chun

Wing chun is a concept-based Chinese martial art and form of self-defense utilizing both striking and grappling while specializing in close-range combat.

Louinn Lota is a Southern California-based martial artist and freelance writer. This is her first appearance in Inside Kung-Fu.

|