|

Eagle claw fighters are still using lessons learned on the battlefield 900 years ago today.

“A lock is as important a tool to a well-rounded fighter as the feint, draw, and stop-hit.“ “A lock is as important a tool to a well-rounded fighter as the feint, draw, and stop-hit.“

“Soldier Fighting focuses upon the maxim that the best defense is a good offense“

The year: A.D. 1130. The place: China. The Southern Song dynasty is trying to survive against the invading Jin armies from the North. The Northern capital already has been captured and the former emperor has been imprisoned in Manchuria. War is raging, with legendary Generals leading their men to death and glory. You stand in the ranks of a mighty army. The horses stamp, snort, and neigh, echoing the nervous energy of the cavalry, the sound of war chariots, and the well-ordered ranks of foot soldiers. You stand ready to fight for home and country, awaiting the order to attack from the man who has prepared you for this battle: your commanding general, Ngok Fei.

General Ngok Fei

Ngok Fei is known as a military genius that not only was innovative in his thinking, but also in his approach to leadership. A healer and scholar, as well as a martial artist and military strategist, General Ngok Fei adopted the six methods for deploying an army:

- Careful Selection of worthy men

- Careful Training of the men

- Justice in rewards and punishments

- Clear Orders

- Strict Discipline, and

- Close Fellowship with his men.

To better prepare his troops for fighting, he developed a system of training and skill-building that was unsurpassed in his day; so much so that 100 of his men were considered the equal of 1,000 soldiers of any other army. The key to creating a highly developed warrior was in the foundation of his training; it was a foundation built around skills known as “Soldier Fighting.”

Northern eagle flaw has continued to train students in the techniques and practical fighting theory developed by its founding father, General Ngok Fei, by using the concepts and principles passed down through Soldier Fighting. Similar to the adaptive hand-to-hand fighting skills of today’s modern soldier, the close-quarters combat “commando fighting” training begun during the Southern Song dynasty’s attempt to survive can enhance the “real-world” effectiveness of any systematized martial training regimen.

In Hong Kong, great grandmaster Ng Wai Nung passed this knowledge to his godson, grandmaster Leung Shum, who, in turn, has brought these concepts to the United States and taught them to the senior students in his ying jow pai organization, including master Kenneth Edwards, head of the Shan Tung Kung Fu, LLC, schools in Southern California.

Soldier Fighting Principles

Soldier Fighting focuses upon the maxim that the best defense is a good offense and is guided by three basic, effective principles. First, a warrior must train to be quick and fluid in his attack. Enter and engage the enemy, intercept and interrupt the attacking force, finish and end the confrontation. The attack should be swift and devastating, with the engagement should be completed in as few moves as possible.

Secondly, engage your opponent until the threat is neutralized. Do not give him opportunities to re-align, adapt, and re-engage. Press forward until the battle is won and you are safely clear of the confrontation.

Thirdly, use full-body power, based upon available terrain, footwork, leverage, and opportune targets. A confrontation is rarely won by a single blow, but a devastating primary attack weakens the ability of the opponent to defend and retaliate, enhances the impact of a secondary and tertiary attack, and can be the difference between successfully dealing with a dangerous situation, or just increasing the eventuality that you will sustain perhaps fatal damage during a prolonged engagement.

These principles create a “usefulness of technique” that bases an attack upon the natural movement of the practitioner as he capitalizes upon the weaknesses of the skill level, physical body and mental preparedness of his opponent. These principles are popular with women interested in overcoming the aggressiveness of a stronger, heavier male opponent.

Soldier Fighting Concepts

Bridging the gap between strategy and effectiveness is accomplished by training specific tactics. If “strategy” is the broad picture, “tactics” are the sharp focus. Many techniques are born out of necessity, and those used by the Song dynasty warrior were no exception. Imagine wearing 55 or 60 pounds of armor, carrying weapons, and having limited fields of vision, because of a helmet and the close proximity of soldiers and war machines surrounding you. To prepare for such challenges and limitations, the emphasis would be on training low, strong kicks and knee strikes, devastating elbows, and deadly finishing locks. These are just three of the many tactical areas in which Soldier Fighting excels.

Kicking

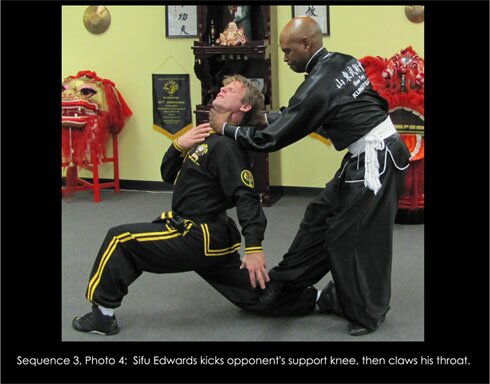

Although many logical and empirical arguments can be made both for and against kicking high in a street altercation, it is generally a good idea to limit kicks only to the height of the midsection and lower. In this way, more force can be generated, less balance is lost, and fewer targets are “opened” to the opponent by the mechanics of actually throwing a kick. Attacking the feet, shins, knees, thighs, groin, and torso with stomps, hidden kicks, knee strikes, and penetrating kicks are goods ways to “enter” into the opponent’s “defensive perimeter” and can disrupt his attack before it gets a chance to start.

Elbows

Once inside an opponent’s defensive perimeter, there are few techniques that can compare to striking with the elbow in power, penetration, and brutality. The correct elbow technique utilizes the core of the body to transmit “full-body power” into the opponent. Using the guidelines taught by Soldier Fighting, a “grid” of five attacking angles is used in conjunction with the elbow strike. Striking across right to left and left to right, striking upward and downward, and then penetrating straight into the opponent provide ample opportunity to “flow” with the attack, and to transfer “stopping power” into the opponent.

Finishing Locks

If a warrior allows an opponent to “disengage” and perhaps “regroup,” then he risks losing the full effectiveness of the primary attack. Therefore, proper training must include the skills needed to “finish” the opponent’s ability to respond to your attack. Northern eagle claw was founded upon, and became renowned for, this ability to seize, grab, lock, break, tear, and disable an opponent. Almost any martial arts style contains at least a simple set of “self-defense” jointlocks, and these should be trained to mastery and used to maintain control of any physical encounter with an assailant.

In Soldier Fighting, such skills as “lock the joint and seal the breath,” “attack the soft tissue,” and “lock, break, and throw” are considered vital “basic training” and are continually drilled and refined until they are second nature. Many do not see the usefulness of such drills, contending that they are too easily recognized and countered. A supreme tenant of “Soldier Fighting” is that a lock is never a “lead in” to an attack, but a follow-up, based upon the opportunities presented during the confrontation.

It is impossible to “grab and lock” a punch thrown by an even average fighter, but it is another story altogether when a lock is applied as a culmination of a devastating defensive attack. For this reason, a lock is as important a tool to a well-rounded fighter as the feint, draw, and stop-hit.

Conclusion

Northern eagle claw is known for its elegant and flowing forms, jumps, kicks, and acrobatics. But it is also home for the brutal and effective battlefield tactical training known as Soldier Fighting. Just as yin contrasts yang, so the seemingly soft “performance” of an eagle claw form contrasts Soldier Fighting. Training the mind and body to combine primal instincts, fluid movement, and total power and effectiveness creates a simple and complete form of close quarters combat, designed not only to be victorious on the battlefield, but also to survive on the street.

When all other options have been exhausted, the one who lands the first punch usually wins the confrontation. So it’s time to hit, and hit hard. Solidify your foundation, enter and engage, intercept and interrupt, and do not stop until the opposition is finished. Tactics evolve with the encounter. Press on to victory with lessons learned on the battlefield almost 900 years ago… in northern eagle claw Soldier Fighting.

Bio:

Kenneth Edwards is a West Coast-based ying jow pai, northern eagle claw instructor under si gung Leung Shum. He can be reached at www.kungfuusa.com David M. Morizot is a Southern California-based freelance writer.

|