|

The Yang fast form is one of the most-effective, yet least-understood fighting sets.

“The Dung fighting form helps you better apply the fa jing energy throughout the classical tai chi postures.” “The Dung fighting form helps you better apply the fa jing energy throughout the classical tai chi postures.”

Often referred to as the “Yang fighting form” or “fast set,” the Dung fighting form is not to be confused with the two-person matching set. While most practitioners know the Chen fast form, the Yang fast form is not as widely practiced by Yang style students.

The Dung form alternates fast and slow movements and stresses “fa jing” energy release throughout its numerous combat postures. Some well-known tai chi practitioners who are not familiar of the Yang fast set even deny its existence. However, its existence and effectiveness are well known by the many students who are fortunate to have learned the set.

History

Born in Hopei province, Dung Ying Jie was a direct student of Yang Chen Fu. During his childhood he was a weak, although scholarly, youth. One day he went to his grandfather’s house, when he met his grandfather's friend, Liu Ying Zhou, who began teaching him the martial arts. Liu was old and could only teach him by verbal instruction. Some time later, Liu brought Dung to see Lee Xiang Yuan. Liu told Dung to bow before Lee and ask to be accepted as a student. He accepted Dung, and when he touched Dung’s arm Dung felt severe pain right down to the bone. Dung knew he was a master. Born in Hopei province, Dung Ying Jie was a direct student of Yang Chen Fu. During his childhood he was a weak, although scholarly, youth. One day he went to his grandfather’s house, when he met his grandfather's friend, Liu Ying Zhou, who began teaching him the martial arts. Liu was old and could only teach him by verbal instruction. Some time later, Liu brought Dung to see Lee Xiang Yuan. Liu told Dung to bow before Lee and ask to be accepted as a student. He accepted Dung, and when he touched Dung’s arm Dung felt severe pain right down to the bone. Dung knew he was a master.

Dung studied with him for two years then went back to his home and opened a kwoon, which accepted all students. Dung had learned several martial arts, but it was tai chi he most loved, for he admired Yang Cheng Fu. Dung wanted to study from Yang but Dung’s friends told him it would be a waste of time because Yang would not teach outside of the family. But Dung felt that if one is sincere one can accomplish anything, and besides that, Yang Lu Chan was not a family member when he learned from Chen Chang Hsing. Yang Cheng Fu accepted him as a student and Dung studied with him for three years.

Dung had hundreds of students all over China. When the Communist took over, Dung moved to Macao. Occasionally he would write books and teach kung-fu to his disciples. They would say when Dung moved, he moved like a dragon. When he was quiet he was like a mountain. Unless you saw him practicing kung-fu you would never believe his high level of skill.

In one tournament, Dung was so calm that when his opponent attacked, Dung tossed him back 10 feet merely with a slight push.

The Form

The Yang fast set is unique to the Dung family. Whether Dung created the set from synthesized boxing and tai chi or learned it directly from Yang Chen Fu is unclear. However, the form’s effectiveness and validity speaks for itself. The form contains high-speed movement and foot pivots and fist pounding, arm slapping and foot stomping. The Yang fast set is unique to the Dung family. Whether Dung created the set from synthesized boxing and tai chi or learned it directly from Yang Chen Fu is unclear. However, the form’s effectiveness and validity speaks for itself. The form contains high-speed movement and foot pivots and fist pounding, arm slapping and foot stomping.

While these characteristics are found in Chen forms, the Yang fast set is nothing like Chen style. Chin na and counter-neutralizing chin na also share a major part of the form integrated throughout the various postures. The set is taught in one fairly long section. Hidden methods of energy release (fa jing) not seen in the slow form are clearly visible in the fighting form.

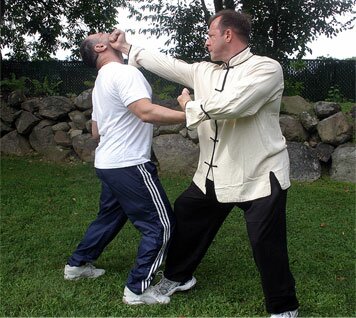

Combat Application

To elaborate on technique breakdown, I will use as an example the Dung form’s brush knee and push posture. In the typical brush knee and push (from any tai chi style) you employ one to deflect and the other to push forward. In the Dung version you use energy release and stamp the rear foot on the ground.

But more importantly, three different hand formations are emphasized at the moment of contact. First, there is the vertical finger spear as the hand and arm thrust forward. Secondly, the fingers pivot upward and the blade of the hand focus as the contact point. And thirdly, the palm turns forward as the hand swivels to bring the palm to the point of contact. For close range, further variation shows the whole forearm to the hand employed as an uprooting push.

Another example is tai chi’s straight punch. In the vertical straight punch there are three phases of the punch. In stage one, the fist is half-closed softly as if you were holding a ping-pong ball in the palm. In stage two, the fist is closed hard and fast and energy is released. In stage three, the fist is tilted upward with fa jing, similar to the way wing chun practitioners crank the fist upward past the moment of impact to focus the force on the last knuckle.

Because tai chi stresses neutralization of incoming force and hollowing of the torso to nullify strikes, the tai chi vertical fist with its three-phase energy release gives the practitioner a tool to strategically counter this neutralization.

Here is a textbook moment of its use: Stage one: You throw the punch fast at your opponent, yet the fist is held soft so that you can maintain the ability to feel and sense whether or not you have a concrete target. As you make contact with the opponent’s abdomen, you feel him moving and hollowing back to minimize the absorption of your strike. Stage two: with your soft fist, you sense his neutralization and flow into him until he reaches the point where he can no longer dissolve by hollowing. Then you tighten your fist, and with a burst of energy, release-energize the punch. Stage three: crank the pinky knuckle upward to maximize the strike.

Dung’s tai chi backfist uses the completely open backhand snapped into a fist just before the moment of contact, causing the knuckles to protrude in a triangular wedge-like fashion. To test this effectiveness on yourself, hold your open hand with the knuckles pressing against your forehead. Now snap your handle into a fist while maintaining contact with your head. The pain and effectiveness of the energy-focusing technique becomes immediately apparent.

Locking and counterlocking share a large portion of the form. The counter chin na techniques tend to be some of the more sophisticated and subtle movements of the form. A movement of the shoulder in the single whip posture may seem insignificant to some, yet to the Dung form practitioner it functions as a release from an elbowlock. A slight turn of the wrist escapes from a hand grab. A withdrawing movement with the arms frees you from the armlock.

Certain classical postures take on different expressions. Cloud hands becomes a right sideward palm strike and a smacking left backhand. Repulse monkey features elbowlock/breaks with the arm held higher and used actively to deflect face-level punches. White cane spreads its wings shows itself as a backhand strike and sideward shuai throw. There are other variations too numerous to list.

In his 1948 book Dung wrote, “Strength is footed at the rear head.” When you are emphasizing fa jing throughout the form, many of the postures will obviously appear different along with the footwork. The body posture tends to be compact, while the footwork is fast and the step is along relative to the postures. The front leg often acts as a break while the rear foot stomps the ground. Because some of the classical postures appear differently, one should not think of them as “the true application of energy,” but rather, as a different expression and another possibility of combat usage from the multifaceted art of tai chi.

Conclusion

For the serious Yang style practitioner, the Dung fighting form helps you upgrade your combat abilities and better apply the fa jing energy throughout the classical tai chi postures.

I was fortunate to have learned the Dung fighting form. That, along with the tai chi whip, an eyebrow-height staff form using flexible wood that was created by Chen Wei Ming (another student of Yang Chen Fu), are two rare Yang forms. It’s important to learn forms from different instructors who are part of the same family tree. Each teacher will offer something that will deepen your understanding of the art.

bio

New York-based Robert Dreeben is a former Inside Kung-Fu “Writer of the Year.”

|